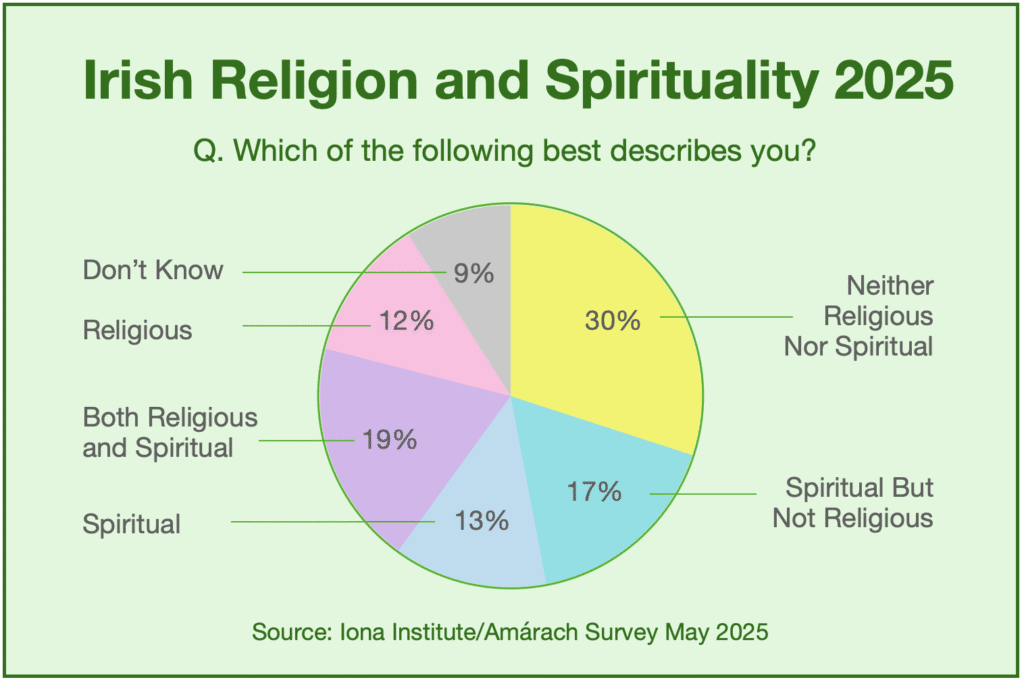

Of every ten Irish people, only one now says they are religious only, three say spiritual only, and another two say they are both. Another three say they are neither, and one doesn’t know. That’s from a recent survey by Amárach for the Iona Institute.

This survey updates a previous Iona/Amárach survey in 2011. Back then, seven in ten said they were Catholic. Today, all forms of religious identification combined are down to just three in ten, two of whom say they are also spiritual.

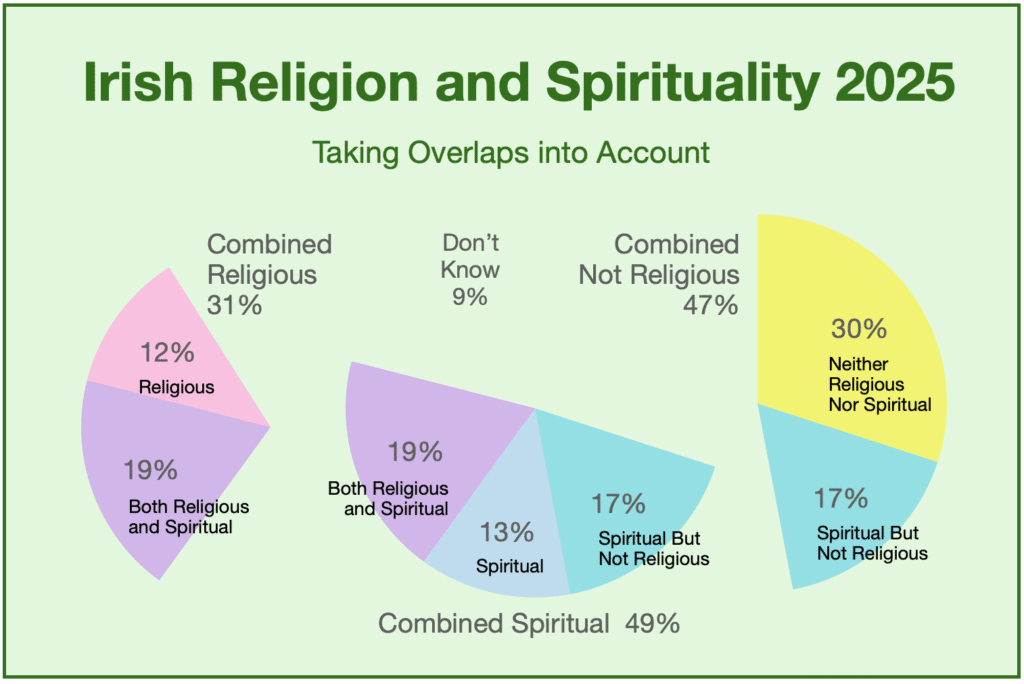

But instead of highlighting this massive decline in religion, the new report combines the figures for religious and spiritual together, even including those who say they are spiritual but not religious.

This allows them to conclude that ‘The majority (61%) of people in Ireland describe themselves as religious and/or spiritual.’ And this is technically true.

But it is just as accurate, and more revealing, to conclude that ‘The vast majority (69%) of people in Ireland do not describe themselves as religious, the exact same proportion who identified as Catholic in 2011.’

The growing impact of spirituality

The 2011 survey didn’t ask about spirituality. This one did, which raised an interesting unasked question. With this nuance added, would many nonreligious people indirectly reveal themselves as spiritual rather than atheist?

This does not seem to have happened. Three in ten now say they are neither religious nor spiritual. Instead, the spiritual option seems to have freed nuanced people from identifying only as religious or not religious.

With some overlaps, nearly half now identify as not religious, another half identify as spiritual, and only three in ten identify as religious. Here’s how those top line figures break down:

- Only 31% identify as religious (either with or without spirituality)

- 49% identify as spiritual (either with or without religion)

- 47% identify as not religious (either with or without spirituality)

- 30% identify as neither religious nor spiritual

- 9% don’t know

So what does this massive culture shift mean for Irish society?

Similar trend in Irish marriages

This survey fits in with recent trends in Irish marriages. This year, the CSO published partial data based on last year’s marriage figures. Atheist Ireland then obtained and published the full breakdown by ceremony type.

Of every ten Irish marriages, four are now secular. This is twice as many as twenty years ago. Within this, Civil Registry marriages are now the most popular. In the past two years alone, they are up from a quarter of all marriages to a third.

Just over a third of Irish marriages are now Christian. This is down from a massive eighty percent twenty years ago. Within this, in the past two years alone, Catholic marriages have dropped from most popular at four in ten, to second place with three in ten.

Almost a quarter of Irish marriages are now some variation of Spiritualist, Pagan, or Celtic. This is up from zero twenty years ago, and up from twenty percent two years ago. These are legally classified as religious, but are very different to traditional religious weddings.

If this trend continues, these could overtake Christian marriages, and be the second most popular type behind Secular.

Iona Institute briefing note on New Age weddings

The Iona Institute produced a briefing note last year on the rapid rise in what it called New Age weddings. This asked: ‘A big question is how the mainstream Churches should respond. How can they re-engage with couples and how far should it go to do so?’

Some extracts from this briefing note include:

‘It is difficult to classify some of these emerging religious organisations but many practice a bespoke type of spirituality tailored to the couple’s desires. They could loosely be described as ‘New Age’, but this is a contested term. (p3)

Citing Heelas and Woodward, Løøv elucidates what she means by New Age by outlining the difference between ‘subjective-life spiritualities’ and ‘life-as-religion’.

- In ‘life-as-religion’ (Catholicism is an example), authority is embedded in a hierarchical structure and theological dogmas, and the individual is expected to adhere to a preordained system of beliefs and values.

- In contrast, subjective-life spiritualities are characterised by an emphasis on the individual self as the authority, agent, and goal of spiritual practices. (p4)

The Pew Research Center has pointed out that many US Christians also hold New Age beliefs, including ‘belief in reincarnation, astrology, psychics and the presence of spiritual energy in physical objects like mountains or trees’. The situation is probably no different in Ireland, with some people not even realising (for example) a belief in reincarnation is incompatible with Christianity. (p4)

What is clear is that it is misleading to describe these broadly New Age organisations as denominations, which implies a degree of adherence to institutional religion that they emphatically reject. (p4)’

These extracts show how institutional religions are uneasy with self-identification and individual choice. That’s one of the core issues that these trends reveal. Let’s continue with more extracts:

‘While increasing secularisation and the impact of several decades of sexual abuse scandals are implicated in the drop in Catholic weddings, there are also several commercial drivers of the phenomenon. [Weddings in venues other than registry offices] did not take place until 2007, when as Carl O’Brien of the Irish Times said, ‘Hotels, castles and country houses [were] queuing up to cash in on changes to marriage laws.’ (p4)

It raises questions for the Christian Churches. Why are people drawn to these ceremonies? What impact is it having on traditional Christian belief? And is there anything the Churches can do to encourage more couples to participate in Christian marriage? (p5)

If, however, we believe as Christians in the Good News, we cannot be sanguine about so many seeking alternative meaning systems, some of which are antithetical to Christianity, at such a crucial transition time as deciding to marry, even if we allow that some are being nudged towards these ceremonies by hotels for commercial reasons. (p6)’

How should we respond to these trends?

The purpose of the Iona Institute, as a registered charity, is to advance and promote the Christian religion, and its social and moral values. Its response to these two developments is interesting.

- In one case, it masks the decline in self-identified Christianity by combining the figures for religious and spiritual together.

- In the other case, it faces the contradictions between Christianity and spiritualism, and asks how the mainstream churches should respond.

Atheist Ireland argues we should acknowledge the reality of where we are, and build from there. Three recent referenda (on marriage equality, abortion, and blasphemy) have shown that the Irish people are broadly two to one in favour of a more secular state. Only about one in three Irish people support traditionally religious positions on social issues.

The Catholic Church no longer controls the minds of the Irish people. But it still benefits from legacy laws and our 1937 Constitution. Our state-funded schools still teach religion as truth. Our Constitution still requires religious oaths to hold the highest offices, including judges and whoever wins the coming presidential election.

It’s time our state caught up with its people. A pluralist people deserves a secular state.